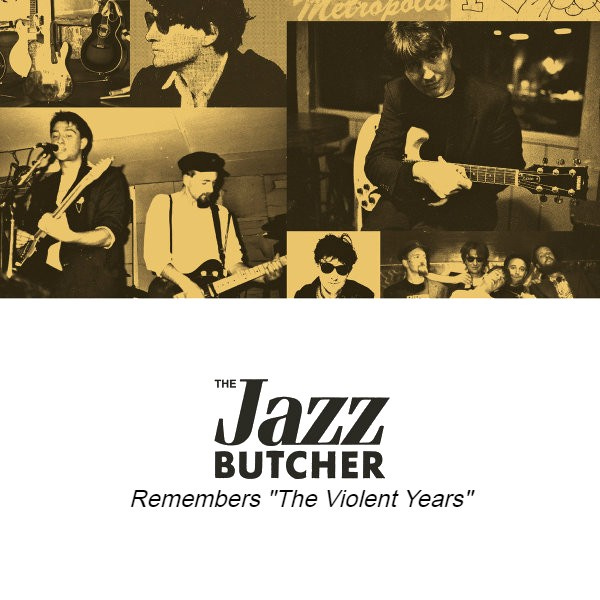

An archived INTERVIEW with Pat Fish - THE JAZZ BUTCHER (1957-2021)

The stories he could tell. Mr. Fish will be sorely missed.

AN INTERVIEW WITH PAT FISH (9.25.2020)

T-BONES: How did you get started writing songs? Was there a song you heard and thought - “I can do that too!”

MR. FISH: You can be hearing the most wonderful music in your head, but if, like me, you can’t write music, then inevitably you can only write what you can pick out on a guitar or a piano or whatever. I was particularly handicapped in this department as a youth because I could only play the flute and the tenor sax, which are hardly great composing tools. Only one note at a time, you understand. In the summer of ’81 I heard a surprise 7” release by Velvet Underground drummer Mo Tucker. She had banged out a version of the old classic “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?”, using multitrack recording to play everything herself. I thought, “Well, if Mo can make a record all by herself with some pretty rudimentary skills, perhaps I could manage it too one day.”

It was that kind of thinking that led me to learn a bit of guitar, and, from there, the songs came. Because I knew not what I was doing, any riff or chord sequence, however basic, felt like magic to me. I was blessed with a twin deck ghetto blaster which had a wonderful design fault: when you copied a cassette, the internal mics

remained open. Having discovered this by accident, I realised that I could bounce between two cassettes to build up primitive little arrangements on tape. In a dismal, lonely three-month spell living in a village at the start of ’82, my silly experiments started to turn into the songs that you can hear on our first album, Bath of Bacon.

So it was a question of process and methodology, rather than any fancy “inspiration.” I followed my nose, made up silly words because I never for a moment thought that anybody other than my closest friends would ever hear this stuff. I kept in mind Eno’s axiom about working within your limitations and I always remembered Mo as well. I

owe her a lot.

T-BONES: During the years on Glass Records, you seem to be trying everything you can out. Was songwriting and recording in the beginning this sort of “land of opportunity” for you?

MR. FISH: I think it’s fair to say that, yes. The recording studio was a great adventure, nothing was off-limits. We were lucky enough to be learning on the job, so, of course, we made a few “schoolboy errors” along the way.

T-BONES: In 1986, your music makes the American transition to Big Time (distributed by the major-label RCA,) how did that feel to suddenly find listeners and even fledgling Alternative and College Radio support over here?

MR. FISH: We spent most of ’85 on the road in Europe, so we were already used to a certain low level of media interest: radio, TV, and so forth. Well into ’86, however, it never crossed our minds that we would ever go and play in America. That seemed unimaginable. When Dave Barker, the boss of Glass Records, told us that we were

going to play there, we didn’t really believe him.

We arrived in New York in the middle of the CMJ conference. It was only when we got there that we discovered that we were in the top ten on the various independent charts of the time. We were entirely unready. “What’s a station ID?” I would say to the legions of trendy young things with fancy recording gear who seemed to pop up

everywhere in our path. It got worse in Canada. Nobody had told us, but we were on a major label up there. I found out when somebody handed me a sheet of paper with “Mercury” printed at the top and an interview schedule that began at 9:00 am. It all seems to come together when you move to the greener pastures of Creation. “Fishcotheque” builds on “Sex and Travel” while revealing that you are never devoting yourself to one “style” of music.

T-BONES: Is it safe to say that the song you wrote was more important than meeting any similarities to the songs of that period?

MR. FISH: Both Dave Barker at Glass and Alan McGee at Creation had sufficient faith in us that there was none of that record company nonsense about trying to make us sound fashionable, or like somebody else successful. They left us to our own devices. There was none of that insidious “You know what we should do?” stuff.

Dave, Alan, and I are interested in making beautiful records rather than “hits.” And sometimes, of course, as Alan has proved, you can do both at once. Our band had friendships with other bands, most of whom sounded nothing like us, but who shared a certain aesthetic and perspective. We didn’t identify with any kind of “movement” or anything like that. We weren’t trying to make records to cause a stir that week. We were trying to make records that would last the listener a long time, that would repay his or her investment.

From the second LP on, our production values had as little in common with the rough, cheap, just-learned-to-play “indie” sound as they did with the big, clattery, soulless cocaine sound of the major record company bands. We weren’t fashionable then and we aren’t fashionable now. But you can put just about any of our records on

today and they’re still listenable, still comprehensible to the modern ear. Unlike, for example, Bogshed. But then, if you want to make a record, it helps if you have an actual song, yeah?

It is possible, of course, to make a classic single more or less by accident in a few frenzied hours in a cheap studio. But something to which people are going to sit down at home and pay attention for half an hour at a time? Give me a break. All the music on Fishcotheque has its roots in Africa. There are obvious things, like

some of the rhythms and the pretty, chiming guitars. And there is also the fact that all the music that we listen to – on our side of the planet, at least - comes from Africa.

T-BONES: Where did the idea for samples come in? They really make the songs stand out

further from the pack?

MR.FISH: The biggest influence here was a single by Steinski and Mass Media called “The Motorcade Sped On”, a stunning assemblage of radio commentary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, brilliantly manipulated into something that can only be described as a great pop song. We played that constantly on the tour bus. Long before I even knew that samplers existed, I used to mess about with tape edits. Late at night in my little music room, I would pull off a particularly nice edit and drunkenly declare myself the Prince of the Pause Button. Out loud.

By 1986, thanks to Big Audio Dynamite, Public Enemy, and the JAMMS (deranged forerunners of the mighty KLF), we knew that samplers were out there, but we didn’t actually encounter one face-to-face until we made Fishcotheque. You only have to listen to “The Best Way” to know how delighted we were about that.

After that, it was samples all the way. We still used to collect them on cassettes and then feed them into the sampler when we arrived at the studio. By “Condition Blue” I was getting into using musical loops as well, something that developed more and more with Sumosonic and ultimately Wilson. I think that – be they loops or voices – nice, scuzzy samples can add real excitement to a mix. For me, dropping cool samples is as much a part of the recording process as a lead guitar overdub, a backing vocal, or a tambourine, and, well used, it can play just as important a role.

Now as “Big Planet Scarey Planet” you grab for an intense worldview, the songs all play differently and you draw some great character sketches in your stories like “Bicycle Kid” and “Line of Death”. Was the goal to broaden your horizons and maybe appear more of a storyteller to your new audience? To be honest, I didn’t know that I had a new audience. We were trying to broaden our horizons, but more in a musical sense. We weren’t very successful, as it goes. The record was made at the start of 1989. We’d been listening to Public Enemy, KRS-1, NWA, DeLa Soul. We were aware of the growing dance scene and not unfamiliar with ecstasy. So we only wanted to make a

psychedelic hip-hop folk-rock protest album for the dancefloor: nothing fancy!

In the end, we collapsed between a number of stools, so I don’t think the album really works particularly well. The most “old-fashioned” songs came out best, I think; simple pop like Bad Dream Lover or The Good Ones; easy African style tunes like Nightmare Being or, rather more frantically, The Word I was Looking For. I’ve never really had the knack of story-telling songs. I’ve tried, but it’s usually pretty clunky stuff. I guess Bicycle Kid was a bit of a lucky one-off in that department, but it was based on a real individual, so no imagination was required, happily. I don’t really “do” imagination. I see myself more as a maker of short, noisy documentaries.

T-BONES: How was that first American tour? Did it influence your writing in ways you could not foresee? Do you still conjure up memories of it when you write today?

MR. FISH: On our first tour in 1986 I think my brain was fully occupied with trying to come to terms with what was happening and cope with the strangeness of it all. We were already familiar with a number of different countries, languages, and cultures, but America and Canada were something entirely new to us. Because we appear to speak the same language (we don’t, of course), a lot of British people think that America is just like a big, hot, prosperous Britain. It’s not. It’s a foreign country and it takes a lot of getting used to. So on that first tour, I wasn’t really up for too much observation; it was more just a question of keeping one’s head above water, getting the job done, and getting out alive.

Then, of course, came all the other tours. I was a bit more comfortable by then, and I had made some friends “on the ground”, as it were. I was a bit more able to open my eyes and take in what was going on around me. As early as 1989 I had already formulated the idea that all I really did was to observe the weirdness of Americans,

Write it down, set it to music and then sell it back to them. I guess “Hysteria” is a good early example of that. It’s about our experiences on the West Coast on our 1988 tour with Downy Mildew and Alex Chilton. I really did sleep through an earthquake.

T-BONES: Into the Nineties we go. What changes from “Scarey” to “Cult of the Basement?”

You had done ballads before, but “Basement” is somewhat muted compared to the

previous albums. “The Onion Field” is just stunning. For all its ease (and familiarity

with the return of the saxophone) “Daycare Nation” mixes the sardonic with

wistfulness.

MR. FISH: I could easily write a book about the year between the making of “Planet” and “Basement.” Perhaps one day I might. The Second Generation JBC (Paul Mulreany on drums; Laurence O’Keefe on bass; Alex Green on tenor sax; Kizzy O’Callaghan on guitar; and me) had been together for some time now. Tour-hardened, we had developed our own collective personality and style; in marked contrast to the well-intentioned but aimless thrashing-about of “Big Planet.” We had our own vibe now. We didn’t have to try.

In September ’89, on the way home from a gig in Sheffield, Kizzy went into a fit, which turned out to be a manifestation of a brain tumour! Kiz was hospitalised a week or two before we were due to start a nine-week US/Canadian tour. We were lucky enough to snare our great friend Richard Formby to play guitar on the tour and

by the time we came home, just before Christmas, we were a tight-knit little group, routinely dangerous on stage and almost entirely impenetrable off it. When we left for America in the autumn, Kizzy had had some surgery and seemed in quite good form. We had no doubt that he would be joining the rest of us in the studio to make the next record in early ’90. When he joined us at the studio it was a terrible shock: he was heavily medicated and obviously struggling badly. We had all been freaking out since Kizzy’s diagnosis, but we had always had faith that he would survive his ordeal. Here, in the studio, in the middle of the countryside in the middle of the winter, we saw what had become of him. Then we started really freaking out.

So I don’t personally see “Cult of the Basement” as “muted” at all; quite the opposite. For me, it’s a mad, sprawling, scrabbling, desperate thing, simultaneously frightened and belligerent, prone to sudden, unpredictable mood swings. Even the things on it that might normally be expected to pass for humour have a funny eye and a bad attitude. And, like an old English folk song, things only get worse as it goes along, finishing with Sister Death. What else?

There was a real “us against the world” feel to the recording sessions, which took place almost entirely in the hours of darkness. The unassuming little tune “Daycare Nation” is actually one of my favourites. It was cooked up in the studio, inspired by Mulreany just hitting that soft little drum pattern. We got it down in one or two takes, Alex added the three tracks of saxophone, and then, finally, I improvised and honed the lyric. Your estimation of the balance between ”sardonic” and “wistful” strikes me as spot-on. Some of the phrases deployed in the lyric may well have begun as hard-hearted, cynical remarks, but I feel that the context, both sonic and lyrical, pushes those phrases to the point of being almost heart-breaking. And it has a Tube train on it. For me, the sound of a London Tube train is one of the most evocative imaginable. Lonely old men in a vast, uncaring city; that was our theme for this one, and I feel that we gave it a decent shot. We should have programmed it after Mister Odd, though. That, if I’m honest, was a schoolboy error. To make matters worse, I didn’t even spot it until almost thirty years after we made the record! Doh!

Not long ago I was rather alarmed to realise that this LP has two songs on it about murder. I had never really considered myself homicidal. The Onion Field is that rare thing, a moment where I exercise the thing that passes for my imagination. Rubbish piano by me, deeply disturbing guitar wailing by Richard. I Came fifth in a Nick Cave impressions contest.

No, but I love “Cult of the Basement”, me. It’s the first record that really captures the sound and spirit of the band at that time. It’s not entertainment; it’s a genuine dispatch from the front line.

T-BONES: Now we wind up with “Condition Blue” where your whole sound comes full circle. Lyrically, you are putting the pieces back together - which is a beautiful thing. I know there is a lot of emotion wrapped up in this record. Looking back on it now as the end of this sequence, if you will, how do to respond to it today?

MR. FISH: Can I be honest? I think it’s an astonishing record. Everybody thinks their kid is a genius and their cat is the prettiest creature that ever lived, but I genuinely do think this is a proper good record. I still play it in order to try and understand it, and it often catches me out or blows me away, just like a “real” LP by a “real” artist. There are some stellar cameos from the likes of Pete Astor, Peter Crouch, Richard Formby, Joe Allen, Alex Lee, and Sumishta Brahm.

I didn’t see “Condition Blue” as the end of any sequence at the time; more like the end of the entire fucking universe. But making “Waiting for the Love Bus” some nine months later was a very interesting “Where do we go from here?” sort of challenge, so I guess there is some virtue in seeing things that way. Fortunately, I had Richard Formby there as my producer. He and I see eye to eye on so many things. Moving on into the “space beyond” was a pleasure with Richard at the controls.

T-BONES: What are your plans for the remainder of 2020, could we see some new songs from

you coming soon?

MR. FISH: My chief objectives for 2020 are to remain alive and solvent. I’ve not really left home since the beginning of March, so I rely on the kindness of strangers to put a dollar or two in the hat when I play one of my little solo sets Live From Fishy Mansions on the Facebook. Those who tune into my little broadcasts will already have heard some new, unrecorded songs. There are more coming along and it’s definitely my intention to make at least one more LP before I hang up my boots. The process is already underway, in fact.

T-BONES: Will there be more reissues on the way? Maybe a rarities package or live highlights?

MR. FISH: December will see the release of the third Fire Records box set, “Doctor

Cholmondley Repents”, a 4 CD set featuring singles, b-sides, compilation tracks,

demos and a really rather fabulous 45 minute live radio session.

Fire Recordings will be releasing “Doctor Cholmondley Repents” on November 12th.

T-BONES Records and Cafe is a full-service fast-casual restaurant and record store in Hattiesburg, MS. We are a member of the Coalition of Independent Music Stores and are the longest-running record store in the state of Mississippi. If you have questions - we have answers … and probably a lot more information just waiting for you at:

tbone@tbonescafe.com

Visit our website for more information and shop in our ONLINE store if you wish.

T-BONES ships the best music all over the United States daily. We also specialize in Special Orders. Let us know what you are looking for - we are thrilled to help.